In a recent comment, a HODINKEE Community member questioned the notion of a “summer watch” – and there is an argument to be made, certainly, that a good watch is not something that is bought for a season, but for the satisfaction it will bring over the years to its original owner, before it is passed down in the fullness of time to their beloved issue, who will never look at it without a softening of the eye as fond and imperishable memories crowd in, etc. etc. However, I like to think that there are times of the year when certain kinds of watches seem, not only more attractive than at other times of year, but positively irresistible. In that vein, I would like to put a thesis to you, gentle reader: the Mido Ocean Star Decompression Timer 1961, which no one can object to referring to as the Rainbow Diver, is one heck of a great summer watch.

This is probably one of the more hotly anticipated summer releases. The news that Swiss fake Mido has been planning on bringing it back has been out for several days, as of this writing, and so far, the consensus seems to be that Mido has hit a home run, and I see no reason to offer a counterargument (which would be difficult to sustain anyway). The original version of this watch was the Powerwind 1000, ref. 5907, from 1961 – it was part of the Ocean Star line, which launched in 1959, right about the time that recreational scuba diving was really taking off around the world. The watch was not in production for all that long, going out of production in 1965. As a result, the Powerwind 1000, whose name refers to its 1,000-feet/300-meter water resistance (this without a screw-down crown, apparently), has become a very popular collectible for dive watch enthusiasts. I don’t follow this particular segment of the vintage collectible watch market tremendously closely, but it looks as if these somewhat rare and very colorful vintage divers retail for close to the $10,000 mark these days – a considerable premium over most other contemporary Mido watches, it would seem.

The new version of the watch has some serious vintage-dive-watch street cred, but it is in other respects – especially technically – a modern watch. The case is stainless steel, 40.5mm, sans display back (naturally), although it does have the original’s Ocean Star starfish, in relief; there is a sapphire box crystal. There is a screw-down crown, one-way turning bezel, and 200-meter water resistance. This is a step down from the 300 meters of the original, which had a one-piece case; Mido offered an unconditional guarantee of water resistance at depth, which they proudly pointed out in the original instruction manual. 200 meters, of course, is more than six hundred feet, which is well below the depths usually reached in recreational scuba diving, so if you want to take a new Ocean Star Decompression Timer underwater, you’re more than covered.

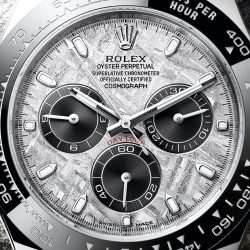

The signature feature of the best copy Ocean Star Decompression Timer (and of course, its ancestor from the 1960s) is the brightly colored decompression table on the dial. The decompression timer is used to tell you how long a decompression stop you’ll need if you exceed the no-decompression limit of staying at 59 feet for 50 minutes. If you’re into dive watches, you probably know the reason you need to decompress if you go below a certain depth for more than a certain time. Recreational scuba divers breathe a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen, and when you dive, you absorb nitrogen into the bloodstream. If you’re not down too far for too long, the amount absorbed will dissipate harmlessly topside, but if you stay deeper longer, enough nitrogen is dissolved into the blood and other body fluids that, if you ascend too fast, bubbles will form (just like taking the top off a soda). This can cause severe pain, which makes the body curl in agony, giving the disease its name: the bends. Bad cases can cause joint and nerve damage and even be fatal.

This is a bad business, but the solution is to stop at a certain minimum safe depth – 3 meters will actually do it, although from what I have read, it is common practice today, depending on your dive profile, to make more than one stop at different depths, as dictated by your dive computer. The whole problem is very interesting; if you make more than one dive per day, you still have to be careful even after you surface, because you have residual nitrogen in your body which must be taken into account when you plan your next dive. Dive tables assume (including the one on this watch) that your entire dive prior to ascent is spent at the indicated depth, but if you are using a modern dive computer, you can shorten decompression time, as going to sixty meters for only five minutes, and then spending the rest of your time at shallower depths, does not require as long a decompression stop as spending the entire dive at maximum depth.

The decompression table on the watch is extremely easy to use. Vintage models would sometimes show depth in meters, sometimes in feet, and sometimes in both; the new watch is calibrated for both meters and feet. Once below the no-deco stop depth limit, you simply look at the maximum depth you will reach – say, 95 feet for the green ring – and then read along the ring clockwise until you reach the point that corresponds to how long you will be at depth. For the 95 feet/30 meters scale, you can see that if you spend 35 minutes at depth, you will be required to take a 15 minute stop at 3 meters. You can also see that if you spend less than 20 minutes at depth, no stop is required as you will not be at depth long enough to absorb enough nitrogen to cause the bends – of course, this assumes, as does the entire table, a so-called square dive profile, in which you descend directly to depth, and then ascend directly from that depth.

For divers and non-divers alike, the presence of the colorful decompression tables offers rather more in the realm of cosmetics than in that of practicality, but it gives the watch a pop and dazzle that seems to incarnate the very notion of a summer watch – especially for anyone who remembers with fondness the elation of the bell on the last day of school that marked the beginning of summer vacation.

If the dial is charmingly anachronistic, the movement is quite modern; inside is the Mido Caliber 80, which has a power reserve of 80 hours. The movement is part of a general trend across the Swatch Group to equip its watches with balance springs offering better resistance to magnetism than conventional Nivarox-type alloys, and to offer longer power reserves as well (even the Swatch now comes equipped with a titanium alloy balance spring, made of an alloy called Nivachron, which offers superior performance as well). The movement is an upgraded version of the ETA C07.621 and is adjusted in three positions; it should offer good performance as well as somewhat better resistance to drifting on its rate than a watch with a standard alloy balance.

I have said that I think this is a great summer watch replica, but I think there is more to it than that. It’s a very striking timepiece which represents a larger part of the history of Mido, and it encourages us to reflect on the hazards inherent to exploration. Nowadays, much of the risk has been taken out of recreational scuba diving, and no sensible person would have it otherwise – especially divers, I am sure – but the somewhat seat-of-your-pants charm of yesteryear still has its appeal and recalls a time when a little risk was an exciting part of the equation, and when the dangers inherent in the activity were – within reason – part of the fun. Even in the dead of winter, I like to think that the aura of derring-do surrounding the era this watch represents will continue to provide satisfaction. After all, most of us will never dive, winter, spring, summer, or fall – and yet we may still wish to entertain pleasant fantasies of exploration and adventure in a brave new world beneath the sea. Why, just imagine what use a certain British naval commander moonlighting for MI6 might have made of one – perhaps whilst in the Bahamas, in the very year the watch debuted, on the trail of a sinister plot to blackmail the nations of the earth with their own atomic bombs – an operation code-named Thunderball.