How one Rolex Datejust Replica Watches UK became my life’s reference point

My first encounter with luxury replica watches uk began before I could tell the time. In our family album, there’s a wedding photo: my father, nervously proud, and on his wrist a flash of yellow gold that anchors the frame. The replica watch was a gift from my grandfather—my mother’s father—presented to my dad on his wedding day, in keeping with a Korean custom of exchanging significant, often expensive timepieces between families. That watch, a yellow‑gold Rolex Datejust Replica with a fluted bezel and linen dial, became my first reference point for what a “real” watch could be: not just an object, but a vessel for history, taste and family lore.

My grandfather died when I was still in elementary school, but stories about him have always travelled freely across our dinner table. He made his life in two demanding arenas: public service and business. He served as Minister of Foreign Affairs during the Park Chung‑hee era, and later led the architecture division of Daewoo, then a major corporate force in South Korea’s rapidly industrialising economy. In family conversations, he wasn’t a caricature of power; he was someone who read late into the night, moved quickly in the morning, and measured his days by what got built and what got negotiated. The Datejust he eventually gave to my father was, I’m told, one of the watches he wore in those years when his calendar was a carousel of flights, banquets and late‑night briefings.

That context matters because of when and where he acquired it. In the 1980s, buying a Rolex Replica Watches in South Korea was not the retail exercise it is today. Official access was limited, disposable income was less widespread, and the idea of spending foreign‑car money on a watch felt distant to most families. The people who did bring home Swiss Clone watches tended to be those who travelled frequently and had the means—and the mindset—to see a watch purchase as both a personal indulgence and a quiet declaration. For my grandfather, it was likely both: a reward for hard miles and a token that said he valued precision, longevity and what a good object can transmit without a single word.

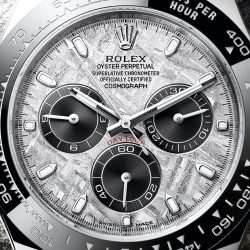

The specifics of the watch are clear enough in our family’s retelling. It’s an 18‑carat yellow‑gold Datejust Replica Watches, with the archetypal fluted bezel and, crucially, a linen dial—the textured, woven‑look surface that plays with light in a way that photos rarely capture. Even as a child, when I managed to sneak a closer look, that dial stuck with me. The sun would hit it and the pattern would seem to hover above the plate, all micro‑shadows and fine relief. It was my first lesson that a watch is not simply a colour or a case shape; it’s a set of choices in proportion and surface that add up to personality.

Then there’s the bracelet—the detail that still raises eyebrows. When my father received the watch as a wedding present, it was paired with an aftermarket yellow‑gold President‑style bracelet. We should be precise here: the “President” bracelet is Rolex’s most famous bracelet design, but it is, in Rolex’s own world, the natural partner of the Day‑Date, not the Datejust. There have been factory combinations and special orders in the brand’s long history, but when one sees a Datejust on a President‑style bracelet, especially in that era, it’s typically the result of an intentional choice outside the standard catalogue. In our case, the choice appears to have been my grandfather’s.

I wish I could ask him why he made it. My father, who doesn’t obsess over replica watches the way I do, can only offer probabilities. Perhaps my grandfather liked the visual weight of the semi‑circular links and the way they read in gold under harsh fluorescent light. Perhaps he associated the silhouette with status—“the President bracelet”—and thought a wedding deserved nothing less. Perhaps, more simply, it was what the jeweller had on hand to make the gift happen in time for the ceremony. Money, during his business prime, was not the constraint. If he had wanted to source a Rolex bracelet, he could have. But he didn’t, and that decision now sits like a comma in our family’s watch sentence: a pause, an inflection, an unresolved choice.

As I grew older and took my own turn down the rabbit hole of horology, the watch shifted from family artifact to case study. The Datejust is, famously, a shape‑shifter. In steel on an Oyster bracelet with a sunray dial, it reads cool and modern. In two‑tone on a Jubilee, it’s sociable and outspoken. In full yellow gold with a linen dial, it’s something else again: dignified, tactile, and determined not to shout its value even as it can’t help being seen. Add the President‑style bracelet, and the message changes by a degree. It’s the difference between a tailored suit and the same suit with a bolder lapel; between a nod and a handshake. Not right or wrong, just different.

That nuance has stayed with me in my work. We often talk about authenticity in Replica Watches UK as if the ideal is to fix a reference in amber: the correct dial, the correct bracelet, the correct clasp stampings, or it “doesn’t count.” There are good reasons for that clarity—collecting requires terms of art, and value depends on them—but family watches live in a different register. They are not case numbers; they’re memory machines. An aftermarket bracelet may ding an auction estimate, but in our house, it simply reads as the way my grandfather wanted this watch to look and feel, the way he wanted it to sit on my father’s wrist on his wedding day. That intention is part of the watch now. It’s as original to our story as any factory part.

The cultural layer adds another dimension. In Korea, giving watches at weddings is not just taste: it’s tradition, a way of exchanging both time and status. The ritual suits mechanical watches well: these are objects that can be maintained, carried forward, and—like a marriage—kept in motion by regular care. My grandfather, who didn’t collect watches in the way that term is used now, still understood that symbolism. He bought many Rolex watches over the years, my father says, not out of niche fascination but because they did a job and did it well. The Datejust, positioned for decades as the reliable, everywhere watch, would have appealed to that mindset. If the Day‑Date was the boardroom watch, the Datejust was the one you could wear from departure lounge to dinner table without missing a beat.

What I didn’t realise as a child was that this single watch—its surfaces and the decisions around it—would shape my own eye. The linen dial taught me to look for texture, not only shine. The fluted bezel taught me that repetition can be elegant, that a pattern executed consistently can become its own form of decoration. The gleam of yellow gold, which in some eras falls in and out of favour, taught me that materials cycle but presence endures. And that President‑style bracelet on a Datejust? It taught me to make room for anomalies, to ask why a choice was made, to trace taste not merely to catalogues but to people and moments.

If you’re expecting an ending in which I “correct” the watch—source an era‑correct Rolex bracelet and return it to factory spec—that’s not this story. To do so would be to subtract one of the few fingerprints my grandfather left on an object I can still hold. I’m not against sympathetic restoration; I believe in good watchmakers, in replacing fatigued parts, in preserving a watch for the next wearer. But I also believe that watches record us. The best thing I can do for this one is to keep it running, keep it in the family, and keep telling the truth about it: that it was chosen, gifted and worn the way it is because someone I admired made a decision I don’t entirely understand.

Every time I see the watch now, I do what all watch people do: I take a breath, note the light, and catalogue what I’m seeing. The linen dial still floats. The fluted bezel still catches every stray beam. The bracelet still looks a half‑step more assertive than a Datejust “should,” and I smile because of it. In that slight mismatch resides the image of my grandfather at a counter somewhere far from home, making a fast, confident choice—the kind that builds buildings, sets policy, and, apparently, puts a President‑style bracelet on a Datejust—before moving on to the next thing.

There’s one question I can’t ask him, and it’s the question that keeps the watch vivid in my mind: Why that bracelet? I’ve come to like not knowing. The question draws me back to the watch again and again, to reconsider it with new eyes, to measure my own taste against his. If I ever pass it on, I hope the next wrist inheriting it will feel the same small friction, the same curiosity. It’s what turns an object into a conversation—one that, like a good automatic, keeps winding as long as someone keeps wearing it.